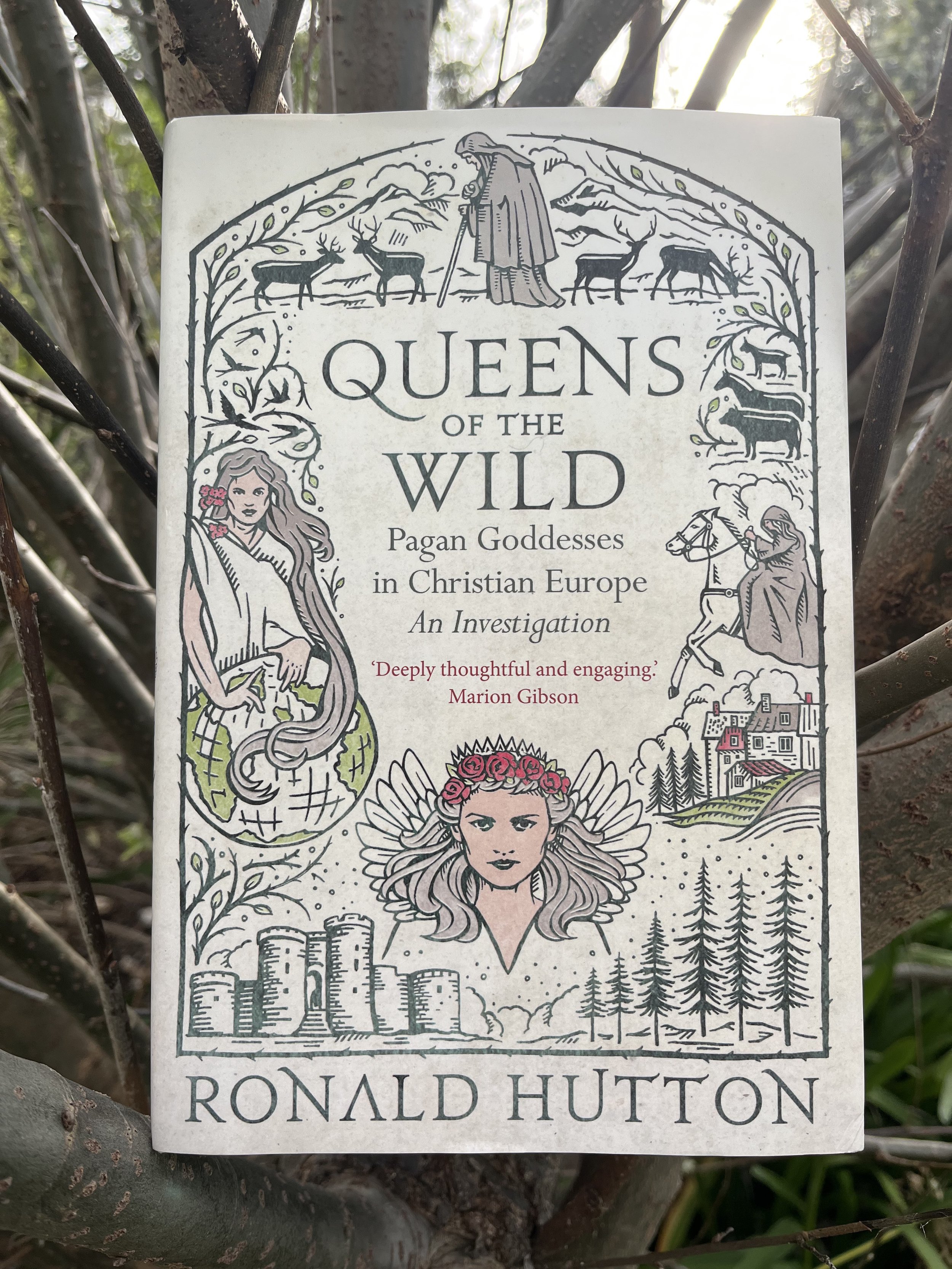

Book Review: Queens of the Wild Pagan Goddesses in Christian Europe: An Investigation by Hutton.

In his new book “Queens of the Wild”, Hutton introduces us to four “Queens of the Wild”, namely, Mother Earth, the Fairy Queen, the Lady of the Night, and the Cailleach, and in the epilogue, he considers a fifth figure, the Green Man. Hutton provides a treasure trove of information on these figures, from the first page to the last, detailing the history of scholarship and cultural expressions they have enjoyed for hundreds of years. Hutton’s central thesis is that these figures are not pre-Christian Gods as many suggest, nor are they Christian, but something outside of both. To support his thesis, he walks us through the history of the figures expertly.

Within the first chapter, Hutton introduces us to the context and key players which ultimately led to the idea of “a paganism gone underground, kept secret and alive in the countryside”, a theory that fuels the conceptualisation of these figures as pre-Christian Gods. Then, in just over forty pages, Hutton charts hundreds of years of scholarly debate so that you come out of it with an understanding that could typically only be borne out of many years of research. Perhaps the most interesting part of this chapter is how Hutton leads the reader thoughtfully through the development of competing theories and their subsequent rise and fall with the publishing of new research, which helps to give a greater understanding of the later chapters.

In the following four chapters, plus the epilogue, Hutton skilfully and beautifully summarises the long history of the five figures listed above but does it in such a way that you easily gain an excellent overview of these figures. Starting with Mother Nature, who he shows was a figure of literature and educated people, accepted into Christian cosmology, falling out of favour and then adopted by environmentalists. Then into the enigmatic Fairy Queen, who began her life as a figure to entertain the noble courts and spread fiercely among the common people, who she would visit and grant boons. Next, the Lady of the Night beginning in the land of the Franks and riding across the night through history. Then the Cailleach rising from disparate stories and traditions across the Gaelic world and morphing into a single figure through the hands of folklorists. And finally, the Green Man, who was seen as the figure behind the vegetal figures on churches, Jack in the Green, the Green Knight and Robin Hood. He tells the stories of the figure's origins, development, re-development and current understandings in a way that adds even more richness and depth to these figures without taking away the magic which draws many of us to them, a skill which is greatly appreciated.

Despite Hutton taking the time to explore and expound his thesis that these figures are not pre-Christian Gods, he emphatically states that this does not reduce their validity or power in the lives of modern worshippers. He explains it well in the excerpt below:

“As we know so little about how the divine operates -if it operates at all - it may well be that those who adopt or have adopted such a religion (or, in less structured form, a spirituality) are actually creating, empowering or contacting 'real' entities.

The trouble only starts if those who embrace such beliefs back-project them upon the past and declare that they are revealing an ancient mystery, or an eternal and universal archetype which once underpinned a global - or even just continent-wide - belief system, or else the truth about ancient or medieval religion…” (page 191).

In the book's conclusion, he gives context to why four out of five figures he explored were female and the importance of that. In addition, he explains how they are not Christian figures and, indeed, something else. Hutton demonstrates throughout the book and makes clear in the conclusion that these figures stood outside of the Christian orthodoxy as strong, effective, and emotionally resonating figures. He says that this proves that the Middle Age and later cultures could envision and live a world outside the Christian cosmology and gender norms of the time. Hutton finally makes the point that calling these figures Pagan or Christian removes the agency of these people and, to me, the figure's agency, who believed in them and found meaning and purpose in their stories. He ends with the point that maybe we need to find a new term outside the binary of Pagan and Christian.

If you are interested in folklore, modern paganism and its origins, and the ideas of agency and legitimacy within modern religions and cultures more broadly, Hutton's “Queens of the Wild” will prove to be thought-provoking, engaging, and a great collection of knowledge.